Citation: Harvey A, “Selecting the Right Primary Container for Injectables in Acute Care”. ONdrugDelivery Magazine, Issue 97 (May 2019), pp 66-69

Alfred Harvey explains why it’s important to select the right primary container presentation – and what can happen if you get it wrong.

“Reducing medical errors, such as

adverse drug events, is a goal for

the entire healthcare ecosystem.”

Understanding the unmet needs of hospitals and care centres is crucial for providing them with impactful solutions. In the healthcare setting, patient safety concerns exist across the entire drug delivery spectrum. Specifically, in an acute care setting, where decisions are often made quickly or under stress, error rates can be at their highest.1 These errors result from normal human faults, cutting corners due to resource constraints and/or an inherent medical product failure. Collectively, drug delivery mistakes create challenges when it comes to maintaining optimal safety for patients and healthcare workers – and can increase clinical operating costs. Differences in primary container options for injectable drugs can add value by offering hospitals and care centres configurations that address universal pain points.

INJECTION-RELATED ADVERSE DRUG EVENTS ARE DANGEROUS AND COSTLY

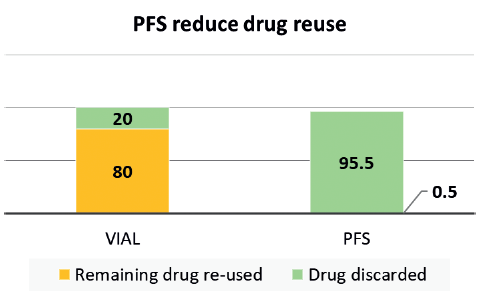

Figure 1: Imaging centre study7 shows 80% imaging agent re-use in vials compared with less than 1% in PFS.

ADEs are dangerous and costly, but those related to administration errors could be limited in the case of injectable drugs by more widespread adoption of primary drug containers that improve workflow, decrease contamination risk and reduce sharps exposure.Reducing medical errors, such as adverse drug events (ADEs), is a goal for the entire healthcare ecosystem. Currently, nearly 5% of hospitalised patients experience a drug-related ADE.2 Of these, injection-related ADEs alone account for US$2.7-5.1 billion (£2.1-3.9 billion) of preventable annual costs to US healthcare payers. On average, this leads to $600,000 per year in extra costs for each hospital, with an additional $72,000 in medical professional liability per hospital.3 The highest error rates (approximately 50%) have been reported in the administration of intravenous medications due to their greater complexity.1

VIAL RE-USE IS A RISKY BUT COMMON PRACTICE

Syringe, vial or ampoule re-use is an existing, risky injection practice that can lead to contamination. For example, a class action lawsuit was settled in 2012 against several endoscopy clinics in Nevada in the US because they were cross-contaminating patients with hepatitis C. The cause was found to be linked to the re-use of vials between patients. The two drug manufacturers supplying the drug involved had also been considered liable as it was argued that the large size of the vials induced a re-use, while the warnings on the vials and on packaging inserts were deemed inadequate.4 Data from the Netherlands suggests that 9-22% of its acute infusions contain some level of microbial contamination, 1-3% of these resulting in infections and increased hospital stays.5 The study showed that using prefilled syringes (PFS) instead of vials reduced the contamination risk to 4%.5 Despite the risks associated with re-use, a 2017 report revealed that more than half of surveyed nurses admitted re-using multidose vials between patients, and almost 25% admitted using the same needle to re-enter the bottle for the same patient. Also reported was that, in an oncology setting, about 20% of oncologists accepted the practice of re-using vials, bottles and bags between patients.6 Similarly, a study focused on vial re-use in an anaesthesia setting showed that about 80% of vials for an imaging agent were re-used between patients.7 In contrast, the same study showed that the re-use went down to less than 1% when the drug was supplied to the anaesthesiologist in a PFS format (Figure 1). These are clear examples where providing medicines in the most “ready to administer” form can help reduce vial/syringe use between patients, decrease cross-contamination and improve safety.

“Drug dosage preparation mistakes with a syringe and vial/ampoule are all too common.”

SAFER FOR PATIENTS AND HEALTHCARE WORKERS

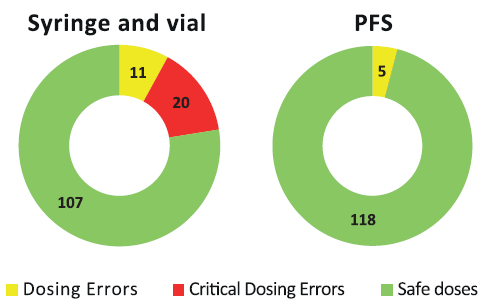

Drug dosage preparation mistakes with a syringe and vial/ampoule are all too common. These can occur from preparing the wrong medicine or the wrong dose.5 While some have minimal effects, critical dosing errors can cause severe problems and even death. A 2015 study looked at total dosing error rates in vials compared with PFS8 (Figure 2). They found that 22% of vial-prepared doses resulted in at least one dosing error, with two-thirds of the errors critical – severely over- or underdosing the patient. In contrast, only 4% of PFS-based syringes resulted in a dosing error event, and none of those were considered critical errors. Through the use of PFS instead of vials, the hospital was able to show a complete elimination of critical errors and a significant reduction in non-critical errors. Also, a 2016 meta-analysis of 46 studies concluded that healthcare worker needle-stick injuries were significantly reduced when PFS were used instead of vials and ampoules.

Figure 2: Dosing errors decrease from 31 total errors with vials to five with PFS in pediatric study.8 Critical errors drop from 20 to zero.

SAVE LABOUR ANDDRUG WASTE COSTS

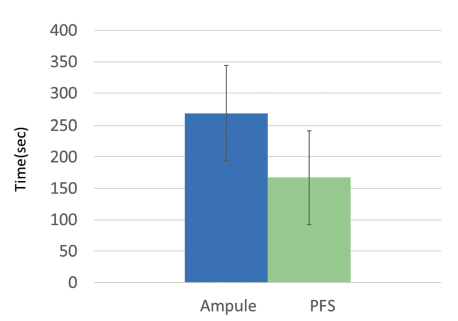

Figure 3: Ampoule preparation took approximately 100 seconds more than when PFS were used (260 seconds versus 157 seconds).10

Like all businesses, hospitals try to reduce costs as much as possible. Labour costs and product waste are two areas where the right drug delivery product can impact their bottom line. For example, patients in medical and surgical units receive an average of 10 injections daily.9 PFS products have been shown to reduce preparation and administration time significantly (Figure 3).10 In an average 150-bed hospital, if 10 injections daily are given to each patient using PFS instead of vials/ampoules, the hospital could save 14,600 hours annually – or $420,000 in labour costs.

Similarly, a 2016 study of drug use in an anaesthesia setting showed that drug waste from discarded vial-based drugs cost institutions around $200,000 per year.11 This cost was eliminated through the use of pre-packaged, PFS. Similarly, a study by a French university’s obstetrics unit compared drug waste between ampoules and PFS. It discovered that switching to PFS for one of its common drugs resulted in a 17% decrease in drug waste – or savings of €0.50 (43p) per patient.12 Lastly, a budget impact analysis was conducted of French hospitals comparing PFS with standard delivery methods, considering medication error and drug waste. Looking only at one drug, atropine, PFS use was modelled to yield a net one-year budget saving of€5.3 million (£4.6 million). It concluded that even though PFS were more expensive upfront, their use would result in significant budget savings in both medical errors and drugs waste.13 As hospitals start to calculate the potential savings PFS can bring, they are likely to look to drug companies that offer these convenient primary containers when they are ready to make a purchase.

“As hospitals start to calculate the potential savings

PFS can bring, they are likely to look to drug companies that offer these convenient primary containers.”

PFS OUTPERFORM VIALS FOR DURABILITY AND FILL VOLUME

Several product recalls have been linked to vials in the past, caused by flaws inherent in the vial manufacturing process.14 Vial glass can delaminate and cause glass particles to appear, reducing glass durability and contaminating the drug.15 These recalls are costly and inconvenient for both drug manufacturers and their customers. The PFS manufacturing process is different from the process for vials, and results in improved glass durability. In fact, PFS outperform glass vials in most test conditions and perform equivalently in others.15 For example, chemicals leaching into or out of a primary container can change the make-up of the drug inside. The inner surfaces of PFS were found to have lower chemical leaching than glass vials.16 Another shared cost for customers and suppliers is the need to over-fill vials with drug. This is done because it is impossible to withdraw 100% of a dose from a vial. The cost of overfilling is either absorbed by the drug company or passed on to its customers. Switching to a PFS as a primary container not only offers a more robust package but also eliminates the need to overfill the container.

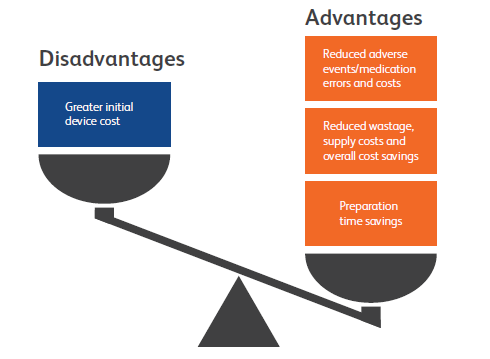

Figure 4: PFS advantages and disadvantages compared with vials. Whilst PFS may cost more upfront, vials are more costly overall.

SINGLE SOLUTION FOR SEVERAL CHALLENGES

Selecting the right primary container presentation for a drug is an important decision that can directly affect customers. As the healthcare industry focuses more on safety, it will be looking for ways to reduce ADEs and needle-stick injuries. When hospitals look to reduce spending, they will target workstream inefficiencies and product waste. In order to continue providing optimal care, they will seek out robust devices with a low likelihood of recall. PFS have shown the ability to address all these needs (Figure 4) and – now that they are available in a variety of formats up to 50 mL in highly resistant glass or advanced plastic – drug companies have many options to meet the needs of acute care hospitals and care centres.

REFERENCES

- Westbrook J, “Errors in the administration of intravenous medications in hospital and the role of correct procedures and nurse experience”. Brit Med J Quality Safety, 2011, Vol 20(12), pp 1027-1034.

- “Medication Errors and Adverse Drug Events”. Patient Safety Primer, US Dept of Health & Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research & Quality, January 2019.

- Lahue B et al, “National Burden of Preventable Adverse Drug Events Associated with Inpatient Injectable Medications: Healthcare and Medical Professional Liability Costs”. Am Health & Drug Benefits, 2012, Vol 5(7), pp 413-422.

- Gargiulo D et al, “Microbiological Contamination of Drugs during Their Administration for Anesthesia in the Operating Room”. Anesthesiology, 2016, Vol 124(4), pp 785-794.

- Larmené-Beld K, “Kant en klare steriliseerbare spuiten”. Presentation to Nederlandse Vereniging voor Farmaciemedewerkers in Ziekenhuizen (NVFZ) Symposium, November 2017.

- Kossover-Smith R, “One needle, one syringe, only one time? A survey of physician and nurse knowledge, attitudes, and practices around injection safety”. Am J Infect Control, 2017, Vol 45(9), pp 1018–1023.

- Vogl T, Wessling J and Buerke B, “An observational study to evaluate the efficiency and safety of ioversol pre-filled syringes compared with ioversol bottles in contrast-enhanced examinations”. Acta Radiologica, 2012, Vol 53(8), pp 914-920.

- Moreira M, “Color-Coded Prefilled Medication Syringes Decrease Time to Delivery and Dosing Error in Simulated Emergency Department Pediatric Resuscitations”. Ann Emerg Med, 2015, Vol 66(2), pp 97-106.

- Jennings B et al, “The nurse’s medication day”. Qual Health Res, 2011, Vol 21(10), pp 1441-1451.

- Adapa R, “Errors during the preparation of drug infusions: a randomized controlled trial”. Br J Anaesth, 2012, Vol 109(5), pp 729-734.

- Atcheson C et al, “Preventable drug waste among anesthesia providers: opportunities for efficiency”. J Clin Anesth, 2016, Vol 30, pp 24-32.

- Bellefleur J, “Use of ephedrine prefilled syringes reduces anesthesia costs”. Annales francaises d’anesthesie et de reanimation, 2009, Vol 28(3), pp 211-214.

- Benhamou D, “Ready-to-use pre-filled syringes of atropine for anaesthesia care in French hospitals – a budget impact analysis”. Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain Medicine, 2017, Vol 36(2), pp 115-121.

- Guadagnino E, Zuccato D, “Delamination propensity of pharmaceutical glass containers by accelerated testing with different extraction media”. PDA J PharmSciTech, 2012, Vol 66(2), pp 116-125.

- Zhao J et al, “Glass delamination: a comparison of the inner surface performance of vials and pre-filled syringes”. AAPS Pharm Sci Tech, 2014, Vol 15(6), pp 1398-1409.

- Jenke D, “Extractables and leachables considerations for prefilled syringes”. Expert Opin Drug Delivery, 2014, Vol 11(10), pp 1591-1600.