To Issue 181

Citation: Miller E, “Shear Relief: Minimising Shear Stress in CGT Production”. ONdrugDelivery, Issue 181 (Dec 2025), pp 40–43.

Dr Ethan Miller examines the manufacturing of cell and gene therapies where shear stress can impact cells and explores strategies to mitigate such damage, helping to ensure that therapies retain their viability, functionality and therapeutic potency from production through to administration.

Cell and gene therapies (CGTs) are a rapidly developing area of technology, and therapies using chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cells, stem cell and other gene-edited cell products are transforming the pharmaceutical landscape. These new therapies essentially exploit cells as living drugs, capable of proliferating and generating a sustained, targeted immune response to treat disease sites in the patient’s body.

CAR T-cell therapy involves engineering a patient’s T-cells to expand in number and generate sustained immune responses, targeting tumours and diseased tissue. Similarly, stem cell therapies use multipotent or pluripotent cells that proliferate and help regenerate damaged tissues. CAR T-cell therapies, such as tisagenlecleucel and axicabtagene ciloleucel, engineer a patient’s T-cells to attack tumours. Viral gene therapies, such as RGX-314 for neovascular age-related macular degeneration, show potential for durable disease control with a single administration. Despite these advances, CGTs face critical challenges during manufacturing, transport and delivery, where maintaining cell viability, phenotype and function remains essential.

Despite advances in CGT delivery and manufacturing, an often-overlooked challenge comes from the mechanical stress experienced by cells during handling. Therapeutic cells are highly mechanosensitive, and exposure to shear forces from fluid flow, tubing, bioreactors, microfluidic devices or injectors can reduce viability, alter phenotype and compromise functional performance, potentially impacting efficacy and safety.

WHY SHEAR STRESS MATTERS FOR CGTs

In fluid-mechanical terms, shear stress (τ) arises when layers of fluid move relative to one another or to adjacent surfaces and can be expressed as the product of fluid viscosity (μ) and shear rate (γ̇); that is, τ = μ × γ̇. In cellular systems, exposure to shear can have profound biological consequences, including morphological deformation, cytoskeletal disruption, membrane perturbation, altered gene expression and reduced viability. Even modest shear rates can produce measurable drift in membrane-bound proteins,1,2 indicating that fluid forces acting near membranes can mechanically perturb membrane-bound entities and thereby impose mechanical stress on the cell surface.

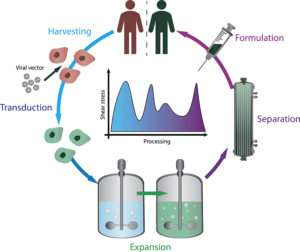

Figure 1: This schematic outlines some major workflow stages in CGT manufacture: harvest and transduction, expansion, separation and final formulation for patient delivery. When unmanaged, shear stress can fluctuate sharply across CGT manufacturing at any of these stages.

During the manufacture and delivery of CGTs, therapeutic cells are exposed to a variety of fluid-mechanical environments that can impose shear stress at multiple stages of processing (Figure 1), potentially impacting viability, phenotype and functional potency. In the initial cell harvest and processing stage, cells are typically collected, subjected to centrifugation and resuspended in media. Here, shear arises during pipetting, aspiration and passage through narrow tubing, with high flow rates generating localised high shear that can deform membranes or disrupt fragile cytoskeletal structures.

During transduction or gene-editing in bioreactors, viral vectors or gene-editing complexes are introduced under mixing conditions; here, even gentle agitation can create gradients of fluid velocity, exposing cells to non-uniform shear. During expansion in stirred-tank or perfusion bioreactors, cells are exposed to varying shear stresses generated by impellers, perfusion flows and sparging (i.e. when oxygen is bubbled through media). These shear stresses can alter cytoskeletal integrity, trigger apoptosis or induce subtle phenotypic drift.

The separation and washing steps, commonly conducted via tubing, pumps and filtration devices, similarly produce localised shear, particularly at constrictions, bends or membrane surfaces, where fluid velocity gradients can be high. Finally, during formulation and delivery, cells are transferred into infusion media; pass through tubing, connectors and injectors; and, ultimately, are administered via catheters or syringes – the high pressures at needle tips or microfluidic sorting channels can produce transient but intense shear spikes.

Collectively, these mechanical exposures can reduce cell viability, alter functional markers and induce apoptotic or stress signalling, potentially reducing the therapeutic potency of the final product, increasing batch-to-batch variability and raising regulatory concerns under GMP and International Council for Harmonisation guidelines.

“AS CGTS SCALE TO MORE COMPLEX PROCESSES, SYSTEMS AND FORMULATIONS, THEIR EXPOSURE TO SHEAR STRESS RISES, INCREASING RISKS TO PRODUCT QUALITY.”

METHODS OF SHEAR STRESS MITIGATION

As CGTs scale to more complex processes, systems and formulations, their exposure to shear stress rises, increasing risks to product quality. Larger bioreactors, higher throughput microfluidic devices and more complex formulations all increase the frequency of shear stress exposure, compounding potential damage on cultured cells (Figure 2). This growing mechanical challenge underscores the need for robust mitigation strategies. Strategies such as optimised flow geometries, controlled infusion rates and protective formulations can help to preserve the functional characteristics of these living therapeutic agents throughout manufacturing and delivery workflows.

Figure 2: Understanding shear is essential to protect sensitive CGT products, preserving their integrity and therapeutic potency during delivery.

For expansion and harvest, platform choice matters. A review of microcarrier and bioreactor strategies by Tsai et al (2021) showed that rocking and fixed-bed platforms produced substantially gentler hydrodynamic environments than conventional stirred-tank reactors, making these low-shear systems attractive for the scale-up of adherent mesenchymal stromal cells (MSCs).3

Sparging during expansion can be another major source of localised high shear, with studies showing that aeration and agitation can depress yields or viability of shear-sensitive viral vectors via and bubble-induced damage.4 Minimising active sparging where possible by using head-space aeration, membrane oxygenation or low-shear mass-transfer strategies can mitigate some of these damaging effects. Alternatively, the use of shear protectants such as Pluronic® F-68 or albumin can be beneficial in processes where bubbles or agitation are unavoidable. Grein et al (2019) document that these surfactant/protein additives can protect cells from interfacial stresses in serum-free processes; but caution is required, as any excipient must be validated for downstream effects on potency and regulatory acceptability.4

Innovation in reactor geometry can deliver low shear without sacrificing scale. Burns et al (2021) describe a 3D-printed lattice, fixed-bed bioreactor that achieves ultra-low wall shear, with computational fluid dynamics (CFD)-predicted shear stresses in the range of between 10-3 and 10-2 Pa ;5 this was much lower than the shear forces that cells are typically exposed to.2 Such low-shear conditions yielded much higher purity and viability MSCs compared with stirred cultures. Their work underscores that structural, fixed-bed or structured-matrix solutions can substantially reduce cumulative shear exposure during expansion and improve downstream product quality.

MARKET-READY MITIGATIONS: REACTORS DESIGNED TO MINIMISE SHEAR

Translating these academic insights into practical solutions, several commercial developers are now introducing next generation, low-shear bioreactors that combine innovative fluidic and structural designs to minimise mechanical stress while maintaining scalability and process control. For example, BioThrust (Aachen, Germany) has introduced a “bionic” bioreactor architecture that replaces conventional sparging with a membrane-based gas transfer and mixing system, enabling bubble-free aeration and gently circulating flow fields even at higher oxygen demands. By decoupling oxygen transfer from impeller speed, the platform enables operators to dial in extremely low-shear conditions without compromising volumetric oxygen transfer. This feature is particularly attractive for induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), which can differentiate into any cell type, and mesenchymal stromal stem cells (MSCs), multipotent cells that support tissue repair, as well as other shear sensitive CGT substrates.

Other companies are pursuing equally innovative, but mechanically distinct, strategies. PBS Biotech (Camarillo, CA, US) has advanced its well-established Vertical-Wheel™ technology, which produces uniform, low-turbulence mixing through a rotating paddle-like wheel; this geometry reduces shear gradients and dead zones while supporting expansion of large aggregates, as demonstrated in numerous iPSC and viral-vector manufacturing programmes. Univercells Technologies (now part of Quantoom Biosciences, Nivelles, Belgium) has taken a different approach with its scale-X™ structured fixed-bed bioreactors, using tightly controlled laminar flow through high-surface-area carriers to achieve high volumetric productivity with minimal fluid shear.

Cytiva (Marlborough, MA, US) and Sartorius (Göttingen, Germany) have re-engineered their single-use stirred-tank bioreactors to accommodate the mechanical sensitivity of CGTs. Cytiva’s XDR and ReadyToProcess platforms incorporate axial-flow impellers with widened blades, magnetically coupled low-shear drives and controlled agitation profiles that maintain mixing while reducing turbulence. Their integrated fluid paths and perfusion modules minimise pulsatile flow, protecting cells during media exchanges and wash steps. Sartorius’s BIOSTAT STR and Univessel SU systems employ low-aspect-ratio impellers, streamlined baffles and films engineered to reduce drag, while automated control of agitation ramps and perfusion rates further limits localised high shear.

“BY EMBEDDING LOW-SHEAR HYDRODYNAMICS INTO BOTH HARDWARE AND CONTROL SYSTEMS, NEW PLATFORMS ALLOW CGT DEVELOPERS TO EFFECTIVELY SCALE PROCESSES WHILE PRESERVING CELL VIABILITY, PHENOTYPE AND POTENCY.”

By embedding low-shear hydrodynamics into both hardware and control systems, new platforms allow CGT developers to effectively scale processes while preserving cell viability, phenotype and potency. Optimising familiar stirred-tank formats, balancing operational efficiency and overall gentler processes come together to further preserve cell viability, phenotype and potency.

Overall, these commercial systems reflect a broader shift in CGT bioprocess engineering – rather than treating shear stress as an unavoidable consequence of scale, manufacturers are now embedding shear-minimising fluid mechanics directly into their reactor architecture, offering platforms that combine gentle handling, closed-system operation and GMP readiness. This convergence of engineering innovation and regulatory alignment is enabling developers to scale shear-sensitive cell products more confidently while maintaining viability, phenotype and long-term functionality.

MITIGATING SHEAR STRESS DURING DELIVERY

Delivery is a critical – and often overlooked – opportunity to minimise shear-related cell loss. Studies show that slower ejection rates, larger-gauge needles and smoothed infusion pulses improve viability and reduce apoptosis in MSCs.6,7 Beyond needle and pump optimisation, innovations such as damped or microfluidic infusion devices, protective formulations, wide-bore tubing and adaptive flow control can further mitigate shear, and are making delivery an active step in preserving CGT viability, phenotype and potency.

Manufacturers can build upon such insights into flow dynamics and needle geometry when engineering novel delivery systems, using CFD and finite element analysis simulation to characterise flow fields, mechanical stresses and formulation–tissue interactions during injection and infusion, allowing for precise understanding of where damaging shear forces arise. This modelling capability is paired with extensive hands-on experience in the design and development of advanced drug delivery systems, from respiratory platforms to autoinjectors and ambulatory infusion pumps, providing a practical understanding of how geometry, actuation, flow control and material choices all influence cell integrity. Combining simulation-led insights with evidence-based device design can help to develop delivery solutions that preserve potency, viability and functional efficacy.

Delivery systems should no longer be considered a passive step but a critical aspect of maintaining CGT product quality. By combining careful device design and controlled infusion protocols, manufacturers can significantly mitigate shear-induced apoptosis, preserve phenotype and improve the functional potency of therapeutic cells at the point of administration.

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES: SHEAR CONTROL AS A KEY TO CGT SUCCESS

Shear forces represent a critical, often underappreciated, factor in the manufacturing and delivery of CGTs. Mechanistic studies have revealed how cells respond to fluid stresses at each stage of development and highlight the importance of integrating process monitoring and controlled handling to mitigate risk. The accelerated adoption of CFD-driven reactor design, “digital-twin” models and artificial intelligence/machine learning for process control will likely emphasise the importance of considering shear effects when optimising critical CGT processes.

Manufacturers should proactively evaluate shear exposure across their workflows, implement monitoring and diagnostic tools, redesign processes and equipment where needed, and embed these considerations within their quality frameworks to ensure consistent product potency. As CGTs scale, controlling shear will likely be key to preserving viability, function and safe delivery. Success demands a holistic approach, including engineering, biology and process control in balance to keep living therapies intact in the turbulent world of CGT manufacturing.

REFERENCES

- Ratajczak AM et al, “Measuring flow-mediated protein drift across stationary supported lipid bilayers”. Biophys J, 2023, Vol 122(9), pp 1720–1731.

- Sasidharan S et al, “Microfluidic measurement of the size and shape of lipid-anchored proteins”. Biophys J, 2024, Vol 123(19), pp 3478–3489.

- Tsai A-C, Pacak CA, “Bioprocessing of Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells: From Planar Culture to Microcarrier-Based Bioreactors”. Bioengineering, 2021, Vol 8(7), p 96.

- Grein TA et al, “Aeration and Shear Stress Are Critical Process Parameters for the Production of Oncolytic Measles Virus”. Front Bioeng Biotechnol, 2019, Vol 7, p78.

- Burns AB et al, “Novel low shear 3D bioreactor for high purity mesenchymal stem cell production”. PLoS ONE, 2021, Vol 16(6), art e0252575.

- Amer M et al, “A Detailed Assessment of Varying Ejection Rate on Delivery Efficiency of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Using Narrow-Bore Needles”. Stem Cells Transl Med, 2016, Vol 5(3), pp 366–378.

- Walker P et al, “Effect of Needle Diameter and Flow Rate on Rat and Human Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Characterization and Viability”. Tissue Eng Part C Methods, 2010, Vol 16(5), pp 989–97.