To Issue 181

Citation: Alzamora J, Sanchez K, Chang E, “Precision Delivery: The Missing Link in Cell & Gene Therapy”. ONdrugDelivery, Issue 181 (Dec 2025), pp 28–31.

Jessica Alzamora, Dr Karla Sanchez and Emily Chang discuss the necessity for precision when delivering cell and gene therapies, explore how this precision can be designed and demonstrated, then go on to describe how a minimum viable product approach to device development can act as a strong predictor of a successful delivery device.

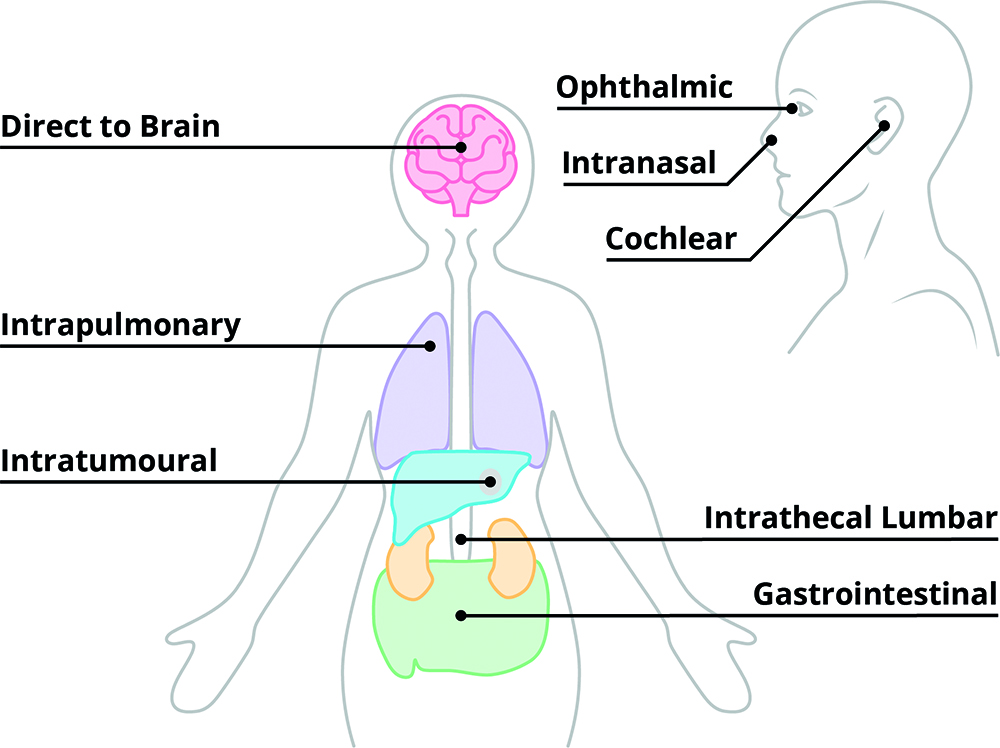

Cell and gene therapies (CGTs) are at the forefront of precision medicine, with the potential to repair or replace faulty genes and cells to treat disease at its biological source. Despite this promise, the success of CGTs depends on one defining factor: precision. Every stage, from designing a vector to delivering it in the body, demands careful control to ensure that the treatment reaches the targeted region and/or cells, at the right dose and with minimal off-target effects (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Commonly targeted delivery sites for CGTs.

“THIS SHOWS THAT THE SUCCESS OF A THERAPY DEPENDS AS MUCH ON HOW IT IS DELIVERED AS WHAT IT DELIVERS – THE THERAPEUTIC EFFECT IS DEPENDENT ON THE ACCURACY OF THE DELIVERY MODALITY.”

A clear example of this reliance on precision comes from a currently available gene therapy to help improve functional vision in patients with an inherited retinal disease due to a genetic mutation. The approved adeno-associated virus 2 (AAV2) gene therapy Luxturna® (voretigene neparvovec, Spark Therapeutics, Philadelphia, PA, US) must be delivered via a highly targeted subretinal injection to ensure that the therapy reaches and acts on the exact layer of cells needed for vision. Even small variations in injection depth or placement can change how effectively it restores function, and incorrect placement can increase the risk of inflammation.1 This shows that the success of a therapy depends as much on how it is delivered as what it delivers – the therapeutic effect is dependent on the accuracy of the delivery modality.

To unlock the full potential of CGTs, the industry must not only consider molecular innovation but also focus equally on the method of precision delivery to expand the pivotal link between discovery and patient benefit. Achieving reproducible precision will determine how effectively these breakthroughs translate from rare success stories into accessible, scalable therapies.

WHERE PRECISION MATTERS MOST IN CGTs

CGTs are not produced in the same way as small molecules or standard biologics. Many programmes are patient-specific or produced in small, labour-intensive batches, with customised biomanufacturing and strict cold chain to preserve vector integrity or cell viability. These constraints make products extremely costly: Luxturna®, for example, is priced at around US$850,000 (£650,000) per patient.2 Given the resource-intensive nature of producing usable material, development teams must prioritise process efficiency and precision from the earliest stages of production.

Potency and safety are also tightly linked. Small deviations in target delivery or poor biodistribution control can provoke serious immune-mediated toxicities,3 among other serious side effects, which is particularly true in gene therapies.4 For instance, intrathecal delivery (administration into the cerebrospinal fluid, e.g. via lumbar injection, allowing direct access to the central nervous system) can have a biodistribution-associated risk that results in dorsal root ganglion inflammation and neuronal degeneration, particularly with higher doses, where neither the therapy’s tropism (affinity with specific cells) nor cerebrospinal fluid dynamics have been fully characterised.4

“PRECISION IN WHERE AND HOW THERAPIES ARE DELIVERED DETERMINES HOW SAFELY IT CAN BE DOSED, HOW CONSISTENTLY IT CAN BE SCALED AND HOW MUCH PRODUCT IS NEEDED TO ACHIEVE A THERAPEUTIC EFFECT.”

Some therapies may only succeed when they are placed with millimetre-scale accuracy. For a rare neurological disorder called aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase deficiency, the AAV2-based therapy Upstaza™ (eladocagene exuparvovec, PTC Therapeutics, Warren, NJ, US), is delivered through stereotactic neurosurgery, which delivers four small infusions into the putamen in a single session (two per hemisphere).5 The product label specifies the route, infusion sites and dosing parameters, as the efficacy of the therapy depends on reaching the correct brain region while avoiding wider systemic exposure. This is precision delivery built directly into the treatment’s design. Furthermore, for one-off or single-administration gene therapies, re-delivery may not be possible (e.g. due to pre-existing antibodies to AAV) or may be considered too risky to conduct (e.g. direct-to-brain administration).

Precision in where and how therapies are delivered determines how safely it can be dosed, how consistently it can be scaled and how much product is needed to achieve a therapeutic effect.

Figure 2: Achieving the correct location, dose and distribution.

WHEN PRECISION BECOMES A MOVING TARGET

Precision is easy to define, in theory, but difficult to achieve in practice. For many CGTs, location, distribution and dose must be defined long before clinical trials begin, yet each is influenced by complex and patient-specific variables (Figure 2). Precision is less critical for ex vivo approaches, such as chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapies, where cells are modified outside of the body prior to intravenous administration. These treatments have demonstrated success, as seen with Kymriah® (tisagenlecleucel, Novartis) and Yescarta® (axicabtagene ciloleucel, Kite Pharma, Santa Monica, CA, US) in haematological malignancies. In contrast, precision becomes far more consequential for in vivo gene and stem cell therapies. What seems simple – such as targeting a specific organ for a rare disease – quickly becomes challenging when teams must decide what level of precision is sufficient in terms of which part of the organ and its diverse cell populations to target for the therapy to be effective.

Location

This challenge is clearly visible in liver-directed AAV therapies, where defining location goes beyond reaching the organ itself. The liver’s intricate vasculature and cell diversity means that vector access and expression vary widely, while efficacy depends on transducing enough hepatocytes without excessive uptake by other cells that may trigger immune responses or reduce potency.6 Achieving this balance relies on optimising the route of administration, delivery site and dose flow control.

Distribution

Parameters such as vector concentration, infusion rate and device (e.g. cannula) geometry determine how the therapy is distributed through the tissue and how reliably it reaches target cells. To manage these interdependencies, computational and experimental modelling are integral throughout development of the therapy and delivery device. By modelling vector flow, convection and uptake in patient-specific anatomy, device developers can predict how a formulation or delivery approach will behave before starting animal studies, or they can refine it alongside these studies. These models enable the integrated team (composed of formulation/modality specialists, device developers and more) to optimise distribution patterns, reduce experimental uncertainty and accelerate iteration, allowing precise delivery to be engineered rather than inferred.

Dose

A clearer understanding of anatomical location and distribution also improves how the team defines and manages dose precision, which ultimately determines efficacy and safety. Dosing CGTs is about far more than volume; it reflects how much active vector or number/type of cells are needed to ensure the desired effect within the target tissue. Achieving precise dosages means controlling both potency and delivery conditions so that the administered quantity can translate into a safe and effective treatment. Advances in data analytics (e.g. vector analysis), flow-controlled infusion and real-time delivery monitoring are helping to define this relationship more accurately, enabling teams to move from empirical dose escalation to evidence-based dose design.

Although device design cannot completely negate biological variability, it can stabilise the physical conditions of delivery in terms of location flow and distribution, reducing the influence of external factors on therapeutic performance. In this sense, delivery systems are an integral and essential part of the therapy’s design; the therapeutic without the device is useless. A minimum viable product (MVP) delivery device is essential even in early-stage therapy development, as it underpins both the predictability and scalability of clinical outcomes, as well as reducing risk to both the patient and therapy programme.

HOW TO DEMONSTRATE PRECISION

If defining precision is difficult, demonstrating it under clinical conditions is even harder. Many CGTs show encouraging results in modelling and in vitro studies, only to encounter unexpected variability once tested in animals or humans. Translating a theoretical understanding of location, dose and delivery pattern into reproducible, in vivo performance remains one of the toughest challenges in the field.

The difficulty often emerges during the transition from therapeutic discovery to device-specific preclinical testing. Early studies may demonstrate vector bioavailability or device function separately, focusing on establishing foundational performance characteristics; however, this separation can limit understanding of how the two interact under physiological conditions. As a result, the first time the full system is tested, typically in animal models, teams may struggle to interpret poor outcomes. The question being: is the issue with the therapy itself or with how it was delivered?

If the delivery device or route is not well characterised before entering in vivo preclinical work, study design, surgical procedures and even success criteria can become ambiguous or have a lack of reproducibility.

Study Design

Preclinical study design therefore becomes the first true test of precision. The chosen route of administration determines not only how the therapy will be delivered, but also which model is appropriate for advancing an MVP approach to device design that supports overall therapy development. For example, a device that matches the therapy development stage and its requirements allows for evidence gathering on the control of delivery – isolating results for therapeutic effectiveness.

Anatomical and physiological differences, particularly in vascular structure, tissue density or organ size, mean that delivery parameters optimised in animals may not translate directly to humans. Building these constraints into the study design early on can help teams interpret results with greater confidence.

Procedural Control

Demonstrating precision also depends on procedural control. Every step, from therapy preparation and handling to administration and post-delivery care, can influence efficacy. For cell therapies, cell sedimentation during preparation or delays between thawing and delivery can alter dose consistency and viability. For gene therapies, infusion rate, device placement and user variability can all shift distribution patterns. Integrating human factors engineering into device and protocol design using procedural expertise helps to standardise these steps, thus improving reproducibility and safety.

Regulatory Scrutiny

Ultimately, preclinical and clinical studies are where precision delivery meets regulatory scrutiny. Demonstrating that a therapy and its delivery system consistently achieve targeted exposure is essential for proving both safety and efficacy. Without an early integrated approach to development of the device, formulation and route of administration, teams risk employing complex and expensive animal models or clinical studies only to discover that the delivery method itself limits their ability to assess therapeutic potential.

Incorporating delivery design and evaluation early in development is therefore not just good engineering – it is a strategic safeguard. Precision that is defined, engineered and tested in parallel with the therapy dramatically increases the chances of reproducible success in the clinic.

“THE FUTURE OF CGTS WILL NOT BE DEFINED SOLELY BY NOVEL VECTORS OR MANUFACTURING BREAKTHROUGHS, BUT BY THE INDUSTRY’S ABILITY TO DELIVER THESE THERAPIES WITH ACCURACY AND CONSISTENCY AT SCALE.”

CONCLUSION: PRECISION DELIVERY IS THE NEXT FRONTIER

The future of CGTs will not be defined solely by novel vectors or manufacturing breakthroughs, but by the industry’s ability to deliver these therapies with accuracy and consistency at scale. As CGTs move towards broader indications, the need for predictable, accessible delivery will only intensify. Achieving precision demands earlier integration of biological, engineering and human factors design, alongside continued investment in modelling and device innovation. Precision delivery bridges the gap between discovery and patient impact, turning theoretical efficacy into real-world benefit.

The lesson is clear: precision delivery is not a supporting technology, but the missing link that will connect scientific ingenuity with clinical and commercial success. Those who master it will define the next era of CGTs.

REFERENCES

- Patel MJ et al, “Surgical Approaches to Retinal Gene Therapy: 2025 Update”. Bioengineering, 2025, Vol 12(10), art 1122.

- “Spark’s gene therapy price tag: $850,000”. News Article, Nature Biotech, Feb 6, 2018.

- Morris EC, Neelapu SS, Giavridis T & Sadelain M, “Cytokine release syndrome and associated neurotoxicity in cancer immunotherapy”. Nature Rev Immunol, 2022, Vol 22(2), pp 85–96.

- Perez BA et al, “Management of Neuroinflammatory Responses to AAV-Mediated Gene Therapies for Neurodegenerative Diseases”. Brain Sci, 2020, Vol 10(2), art 119.

- “Upstaza (eladocagene exuparvovec)”. Web Page, EU EMA, accessed November 2025.

- Cao D et al, “Innate Immune Sensing of Adeno-Associated Virus Vectors”. Hum Gene Ther, 2024, Vol 35(13–14), pp 451–463.