To Issue 181

Citation: Chambers M, “Revealing the Frontier: Drug Delivery Challenges and Innovations in Ocular Gene Therapy”. ONdrugDelivery, Issue 181 (Dec 2025), pp 60–63.

Dr Max Chambers discusses novel approaches for delivering ocular gene therapies, summarising the challenges and benefits of various delivery routes and exploring the devices used to successfully improve vision.

“THE SUCCESS OF THESE THERAPIES HINGES NOT ONLY ON THE GENETIC PAYLOAD BUT, CRITICALLY, ON HOW AND WHERE IT IS DELIVERED.”

Eyesight is precious and taking care of it is crucially important, not just to patients, but also to the healthcare systems that support it. The eye presents a number of advantages for the administration of drugs. It is an immune-privileged environment, having no lymphatic vessels, which results in a lower rate of adverse responses compared with systemic administration, while providing a good therapeutic effect from relatively low drug doses.

Gene therapy has emerged as one of the most promising frontiers in ophthalmology as a treatment modality for inherited or acquired diseases, from inherited retinal disorders (IRDs) to age-related macular degeneration (AMD) and diabetic retinopathy. Current treatments for these diseases often involve periodic intravitreal injections, which places a burden on both patients and clinics. As such, opportunities for “one-and-done” treatments for ocular diseases have attracted considerable investment due to their potential to bring transformative benefits for patients. However, the success of these therapies hinges not only on the genetic payload but, critically, on how and where it is delivered.

OPHTHALMIC GENE THERAPIES

Gene therapies in ophthalmology can be broadly categorised into two types:

- Gene Replacement Therapies: These aim to correct defective genes in IRDs, such as RPE65-related retinal dystrophy.

- Therapeutic Gene Therapies: These transform the eye into a bio-factory to produce therapeutic proteins, such as anti-vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) agents for wet AMD.

While IRDs often involve small patient populations and severe outcomes such as blindness, AMD affects millions of people and requires scalable solutions. The delivery method must be tailored to the disease, the patient and the therapeutic goal. Vectors to deliver genetic material to cells are most often viruses, such as adeno-associated virus (AAV) or lentivirus, but lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) are currently the subject of increasing investigations due to their association with lower immune reactions and potentially improved targeting – the design of gene therapy vectors alone is challenging and huge in scope.

DELIVERY ROUTES FOR OPHTHALMIC GENE THERAPIES – THE TRADE-OFFS AND TECHNICAL BARRIERS

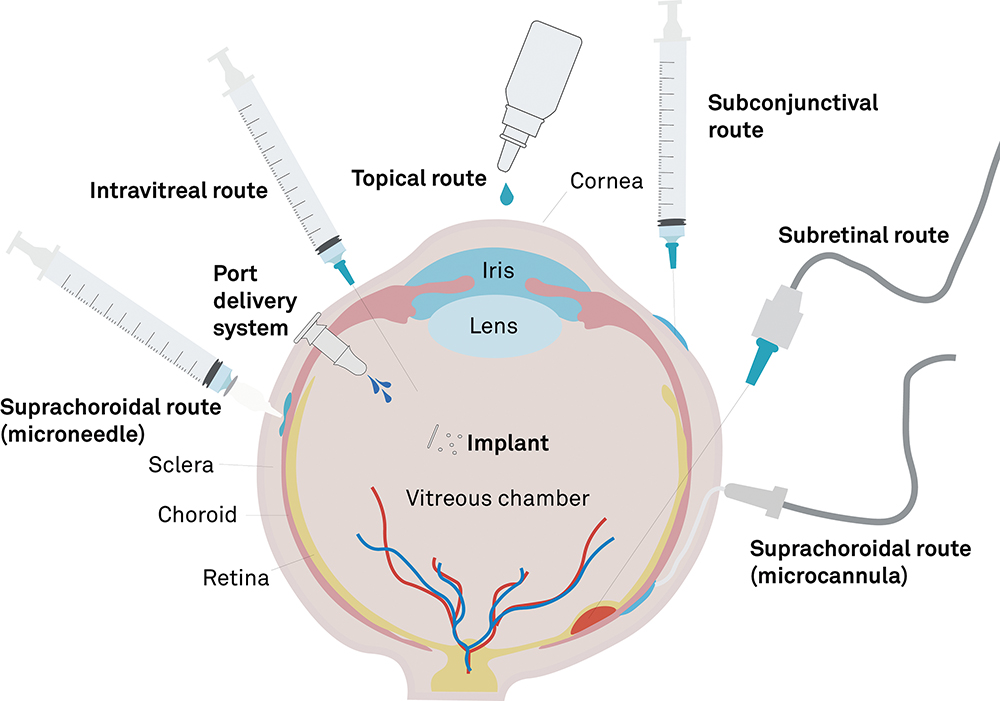

Many people have, at some point, used an eye treatment in the form of eye drops or an ocular spray. However, vectors for gene therapies are too large to traverse the sclera and reach the deep structures of the eye, so more invasive delivery methods are required. There are four main approaches for delivering ocular gene therapies: intravitreal therapy (IVT), subretinal (SR) delivery, implants and suprachoroidal (SC) delivery (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Drug delivery to the eye.

Intravitreal Therapy

“DELIVERY VECTORS MUST DIFFUSE OVER A CONSIDERABLE DISTANCE THROUGH THE VITREOUS HUMOUR TO REACH THE THERAPEUTIC SITE – WHILE AVOIDING NEUTRALISATION BY ANTIBODIES, TRAVERSING THE INNER LIMITING MEMBRANE AND SUCCESSFULLY DELIVERING A TRANSGENE TO THE NUCLEUS OF EACH TARGET CELL.”

IVT has been the common choice for ocular delivery for decades and is widely used for delivering biologics such as anti-VEGF agents to treat AMD. It is minimally invasive, can be performed in outpatient settings and has a good safety profile historically. An IVT delivery device may be as simple as a needle and syringe, making the procedure easily accessible. However, there are challenges with the efficacy of gene therapies delivered by IVT.1 Delivery vectors must diffuse over a considerable distance through the vitreous humour to reach the therapeutic site – while avoiding neutralisation by antibodies, traversing the inner limiting membrane and successfully delivering a transgene to the nucleus of each target cell.

These challenges can pose a barrier to successful development of ocular gene therapies. For example, a Phase I trial of the drug AAV2-sFLT01, an IVT-delivered therapy for neovascular AMD, originally under development by Sanofi Genzyme (Cambridge, MA, US), showed a good safety profile at all doses, but development was halted due to poor efficacy.2

The work has been done to design vectors that improve performance in IVT-delivered gene therapies by engineering vectors with enhanced immune resistance and membrane penetration, but the challenges are still significant. Currently, it appears that there are no IVT therapies that can match the efficacy of SR or SC delivery.

“DIRECT INJECTION TO THE RETINA PROVIDES A HIGH DRUG LOAD AT THE TARGET SITE, ENSURING HIGH TRANSDUCTION EFFICIENCY AND LOCALISED GENE EXPRESSION LIMITED

TO THE NEIGHBOURHOOD OF THE BOLUS, THEREBY PROVIDING SUPERB PRECISION FOR TARGETED THERAPIES.”

Subretinal Injection

SR delivery is the gold standard for the precise targeting of retinal cells to deliver gene therapies. The technique is performed with a specialist cannula via a transscleral, transvitreous route or by passing a cannula through the SC space, delivering a bolus between the neurosensory retina (NR) and the retinal pigment epithelium (RPE). The procedure must be performed in-theatre, requiring a vitrectomy prior to the injection, however, it presents some distinct advantages over the less complex IVT approach. Direct injection to the retina provides a high drug load at the target site, ensuring high transduction efficiency and localised gene expression limited to the neighbourhood of the bolus, thereby providing superb precision for targeted therapies.

However, SR injection carries a higher risk of retinal detachment than other delivery techniques. Injecting a fluid bolus into delicate organic structures subjects them to mechanical stress and this technique necessitates some degree of detachment between the NR and RPE. This separation is usually transient, as the bolus is absorbed over time, but it still represents a real risk to patient vision. There are also logistical challenges with SR injection, since its surgical requirements are resource-intensive and non-scalable. The issue with scalability is outlined by an industry specialist: “For large gene therapy products [for IRDs], if the total population is 2000 patients worldwide, you do two surgeries a week. Compare that to something like AMD and you’re doing 75,000 procedures a year, then is there enough operating room capacity?”

Suprachoroidal Injection

SC delivery presents a compromise between the procedurally simple but less efficacious IVT, and the more complex but targeted SR delivery. The key distinguishing feature of this approach is the delivery of a bolus into the SC space – a virtual space between the sclera and the choroid. Once inside the SC space, the therapy flows around the eye, contacting anatomical structures adjacent to the choroid. The technique may be less invasive than IVT or SR delivery, while providing access to deep structures of the eye and a broader distribution of the therapy across those structures.

There is great potential in this approach, but the devices designed for consistent success are still relatively new, and SC delivery is still undergoing thorough investigation in clinical trials. While clinical data is still emerging, companies have paused SC programmes due to concerns of immune reactions. The route’s success will depend on reproducibility, safety and clinician familiarity. Andrew Osbourne of Ikarovec (Norwich, UK) describes SC delivery by saying: “If the SC approach can combine the precise cell targeting of an SR injection with the ease of administration of an intravitreal one, that’s the sweet spot where it truly stands out”.

FORMULATION AND DOSING STRATEGIES

All successful drug deliveries must holistically consider technique, formulation and delivery device, and gene therapies are no different. Gene therapy formulations are complex – they must balance manufacturability, biological efficacy, stability for cold-chain storage, transport and deliverability for the chosen approach. Understanding how formulation rheology affects deliverability and dosing is essential. For example, viscous formulations are inappropriate for IVT, as they slow diffusion and mixing in the vitreous humour, but viscous formulations are preferable for SC delivery, as they offer better control over injectate spread in the SC space and are associated with lower interference with vision after the procedure.

Viruses and LNPs also require additional considerations due to their large size relative to biologics and small molecules. These vectors require high multiplicity of infection to ensure transduction, which often necessitates bolus dosing; however, high viral or LNP loads are more likely to induce an immune response. They are also sensitive to shear forces and will degrade if subjected to excess stress. This places limits on formulation viscosity, injection rate and delivery time, all of which impact the patient experience.

DEVICE DESIGN

The success of ocular gene therapies heavily depends on the devices used for delivery. Devices for IVT are conceptually simple – a syringe and narrow-gauge needle is used, typically 30G for injections of non-colloidal drugs or 27G for suspensions.3 There are also commercially available accessory devices to aid positioning, such as Precivia® from Veni Vidi Medical (Halifax, UK).4

SR injections require specialised devices consisting of cannulas that are sufficiently long to traverse the vitreous cavity or pass through the SC space, and are very narrow to limit procedural trauma – often 38G to 41G – with even narrower tips to aid retinal penetration. These cannulas are connected to a syringe or extension line for manual delivery, or may be incorporated into a vitrectomy machine for automated pneumatic control. There is some overlap between devices for SR and SC delivery, such as the Orbit® Subretinal Delivery System by Gyroscope Therapeutics (London, UK), where flexible cannulas can be deployed to traverse the SC space and puncture the retina from the rear side.

In principle, SC delivery devices can be similar to those used for IVT, and common needle and syringe systems are still used. However, accurate freehand positioning of a needle within a few tens of micrometres of a sensitive organ is a considerable challenge and requires highly trained clinicians to execute correctly. Catheter-based devices have been developed to address this, such as a new device developed by Everads Therapy (Tel Aviv, Israel).5 Advanced microneedle systems are also under development for SC delivery, such as the Bella-Vue from Uneedle (Enschede, The Netherlands),6 which uses very short narrow-gauge needles to control penetration depth through the sclera. Laura Vaux of Ikarovec says: “If the suprachoroidal approach can reach the posterior segment and achieve broad transduction across the RPE and surrounding sclera, it delivers both the reach and precision needed for effective gene therapy”.

Many of these devices share similar challenges for gene therapy delivery, foremost of which is the requirement for accurate placement and drug spread. There is little distribution control during IVT delivery, but for SR and SC delivery, ensuring that the devices are suited to the rheological characteristics of the formulation is crucial for effective treatment.

PATIENT AND CLINICIAN CONSIDERATIONS

“THE BALANCE TO STRIKE IS BETWEEN CONTINUOUS BUT LESS INVASIVE TREATMENTS AND A SINGLE TREATMENT THAT CARRIES GREATER RISK OF COMPLICATIONS, BUT COULD PROVIDE ENORMOUS BENEFIT ACROSS A PATIENT’S EXPECTED LIFETIME.”

The patient experience is central to the success of any therapy. Patients prefer low-risk, low-pain procedures, but are willing to accept more invasive methods if the vision outcomes are significantly better. The balance to strike is between continuous but less invasive treatments and a single treatment that carries greater risk of complications, but could provide enormous benefit across a patient’s expected lifetime. In either case, an understanding of patient needs and timescales is critical. To summarise from an industry specialist, “Ideally, you want to do a gene therapy to help preserve the retina before it is destroyed. Once the cells are dead, gene therapy is not going to help”.

Clinicians, meanwhile, prefer well-understood procedures with low complication rates. IVT is widely accepted because of its procedural simplicity, with expert clinicians able to perform multiple IVT injections per hour. SR and SC injections require additional training and confidence with the technology, so device usability and reproducibility are key to bridging the gap towards adoption for these more advanced techniques. Andrew Osborne of Ikarovec observes that: “From a technical perspective and to enable widespread adoption, clinicians are likely to prefer an office-based delivery approach that is familiar, consistent and reliable”.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS FOR INNOVATION

The future of ocular gene therapy lies in technological convergence. Artificial intelligence (AI) is already being used to design synthetic vectors with reduced immunogenicity. Non-viral delivery methods, such as optimised LNPs and naked DNA or RNA fragments, offer alternatives to traditional viral vectors. New AI, augmented reality and virtual reality tools, such as the EyeSi Simulator at the Royal College of Ophthalmologists in London (UK), are also providing a platform to train clinicians without the need for theatre time or expensive drugs.7

Inducible gene therapies, which allow for on/off control and dose modulation, are a similar exciting innovation, where the dose can be modulated by systemically delivered excipients. This level of control may increase efficacy, reduce the rate of immunological adverse events and reduce long-term stress on retinal cells, while also providing a dose at an optimal rate for transduction efficiency. However, such treatments are early in development and have not yet made the transition into ophthalmology. They also require the patient to make additional clinic visits, which may dampen some of the benefits of “one-and-done” treatments.

“PATIENTS WILL WANT TREATMENTS THAT

WORK AS EFFECTIVELY AS POSSIBLE, WHILE MINIMISING PROCEDURAL RISK AND OFF-TARGET COMPLICATIONS. SC DELIVERY OFFERS A POTENTIAL ADVANTAGE IN ACHIEVING THAT BALANCE COMPARED WITH INTRAVITREAL OR SR APPROACHES.”

CONCLUSION

Drug delivery is the linchpin of ocular gene therapy. The choice of route, formulation and delivery device determines not only the efficacy but also scalability, safety and patient experience. Andrew Osbourne of Ikarovec summarises this experience: “Patients will want treatments that work as effectively as possible, while minimising procedural risk and off-target complications. SC delivery offers a potential advantage in achieving that balance compared with intravitreal or SR approaches”. The techniques of IVT, SR delivery and SC delivery require differing devices. With the latter two being the more novel approaches, additional training will be required for clinicians, as well as hospitals that are willing to adopt these approaches.

These challenges are not insurmountable, but device and therapy development demand a holistic approach. As ophthalmic gene therapies mature, collaboration between biotech innovators, clinicians, regulators and device manufacturers will be essential. The goal is not just to deliver gene therapies but to deliver clear vision, safely and effectively, to millions of patients worldwide.

REFERENCES

- Ross M & Ofri R, “The future of retinal gene therapy: Evolving from subretinal to intravitreal vector delivery”. Neural Regeneration Research, 2021, Vol 16(9), pp 1751–1759.

- Heier JS et al, “Intravitreous injection of AAV2-sFLT01 in patients with advanced neovascular age-related macular degeneration: A Phase I, open-label trial”. Lancet, 2017, Vol 390(10089), pp 50–61.

- “Intravitreal injection therapy”. Ophthalmic Service Guidance, Royal College of Ophthalmologists, Aug 2018.

- “Precivia® Device”. Company Web Page, Veni Vidi Medical, accessed Nov 2025.

- “Our technology”. Company Web Page, Everads Therapy, accessed Nov 2025.

- “Suprachoroidal injection”. Company Web Page, Uneedle, accessed Nov 2025.

- “EYESi ophthalmic surgical simulators”. Web Page, Royal Co